Whether in California’s southern farming communities or an urban center up north, the coronavirus pandemic is keeping hungry children from the food they need.

And that’s due to a number of factors.

“It’s access. It’s language barriers. It’s finances,” explained John Sasaki, the Oakland Unified School District’s communications director.

A number of families in Oakland lack access to the internet for alerts about feeding sites, and many don’t have the funds or transportation to even reach them. This is particularly true for the district’s Hispanic community, in which 87% of children depend on the meals they receive at school.

Marcus Alonzo has seen the same population impacted in the rural farming community of the Coachella Valley Unified School. Delivering meals to isolated families has been an eye-opener for him and the food service team he directs.

“Before COVID-19, I never went out into these communities,” he shared. “You feed everybody from school, so you don’t know where all these kids come from. I now know that, for a lot of these children, probably the only healthy meals that they get are at school.”

The pandemic has hit both Oakland and Coachella particularly hard. At one school in Oakland, Sasaki found that more than 80% of the families had lost one job in the household, and more than 60% had lost two.

“Mom and dad had lost jobs,” he said. “The need was great already, but now it’s just gone through the roof. Our families are struggling right now.”

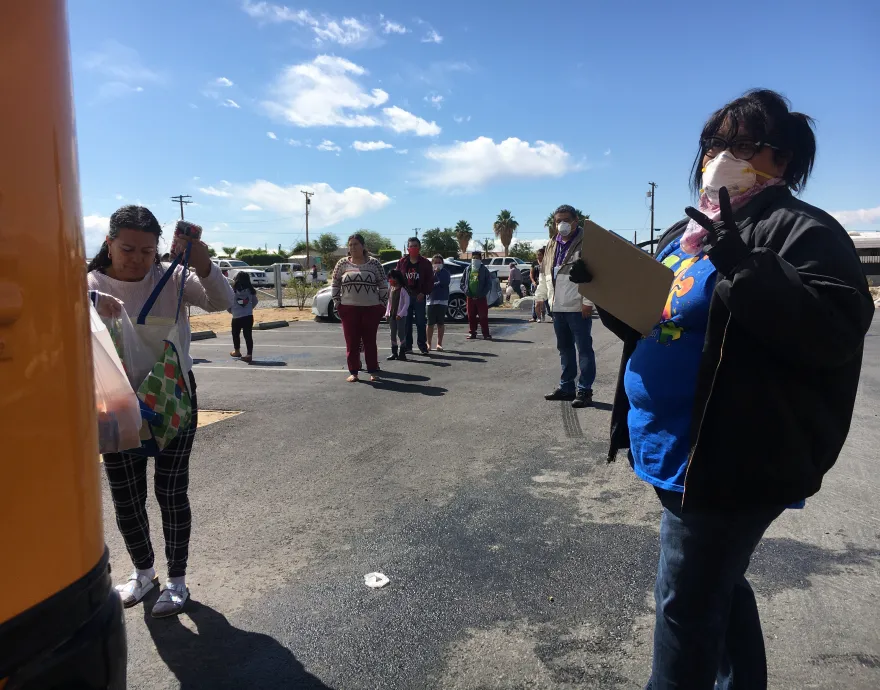

In Coachella, where Hispanic students represent 97% of the district, migrant farming families are especially vulnerable – and the community is rallying to help.

“They don’t have healthcare. One community doesn't even have potable drinking water. With the crisis, I don't think they even know where their next little bit of money is going to come from,” Alonzo said. “It's really opened up a lot of eyes of people within our district.”

When the crisis hit and schools closed, Alonzo and his team took just three days to shift their cafeteria-based operations to reach hungry kids through feeding sites and meal deliveries by school bus.

They’re now averaging 100,000 free, nutritious meals a week using just more than a third of their regular staff. Many are being kept home due to risk of coronavirus exposure. But Alonzo’s team is taking great pride in the work.

“I’ve seen a lot of gratitude from the kids and the parents, and even the grandparents that are raising these kids. They're very grateful,” he shared. “We're doing something valuable for the community.”

Sasaki is seeing much of the same gratitude – and need – with the district’s mobile food truck deliveries and its 12 feeding sites, through which they’re serving some 100,000 and 75,000 meals every Monday and Thursday to help kids eat through the week.

“At one of our schools, a father of four came to get food for his kids,” he said. “He left with a box of 36 meals – nine of each for the four kids – and he carried that box on foot all the way home. I can’t say enough about the need.”

Despite the success of both districts’ efforts, Sasaki points out that childhood hunger in the United States goes well beyond this crisis, and that it’s going to take the work of thousands of heroes to help feed hungry rural, urban and suburban kids alike.

“Whether a child has enough to eat should not be dependent on the zip code they’re born into, the financial challenges that their parents have,” he said. “If our kids didn’t have this resource, we don’t know where they’d be eating, honestly, especially in a time like this.”

Join us in sending a gratitude message to Marcus Alonzo, John Sasaki and other heroes here.