“The Constitution said that everybody has equal rights and justice. You have to make that come about. They are not going to give it to you.”

This quote illustrates Larry Itliong’s often straightforward personality and desire to fight for justice for everybody. Itliong’s legacy for the equality of immigrants and farmers is often understated.

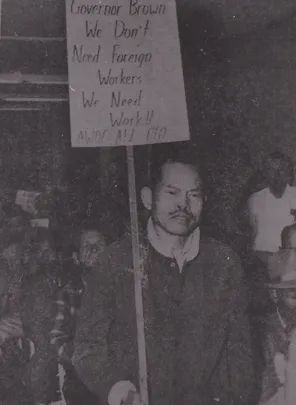

The 1965 Delano Grape Strike, organized and led by Itliong, is recognized as a milestone in the Civil Rights Movement. Workers took on one of the mightiest industries in California, and after a struggle that lasted over five years, they secured rights for thousands of workers and inspired generations of Chicano and Filipino activists.

The strike revolutionized farm labor in America, creating protections for farmworkers and immigrants, whose families and children are at higher risk of experiencing hunger even today.

However, Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez are celebrated as the leaders of the strike. Every March 31, we commemorate the legacy of Chavez and Huerta, and even President Biden keeps a bust of Chavez in the Oval Office.

But we often forget about the important role that Filipino and Filipino-Americans had in the Delano Grape Strike. This Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month, we highlight Larry Itliong, who along with a group of Filipino immigrants, started the strike and later convinced Mexican American workers, led by Huerta and Chavez, to join. They formed an unprecedented coalition that was essential to the success of the strike, and the growth of California’s economy.

As explained by the late activist Dawn Mabalon, “Filipino and Mexican immigrants and their families turned California into the seventh-largest economy in the world. There are still Filipinos working in the fields and sorting asparagus with Mexican immigrants.”

Itliong migrated to the U.S. from the Philippines— then a U.S. colony— as a teenager who dreamed of becoming an attorney to protect the poor. The conditions of poverty and discrimination didn’t allow him to seek the education he dreamed of, and pushed him instead to work in salmon canneries in Alaska.

His desire to serve others did not falter. He quickly organized workers, forming the Alaska Cannery Workers Union and led multiple labor efforts throughout the West Coast.

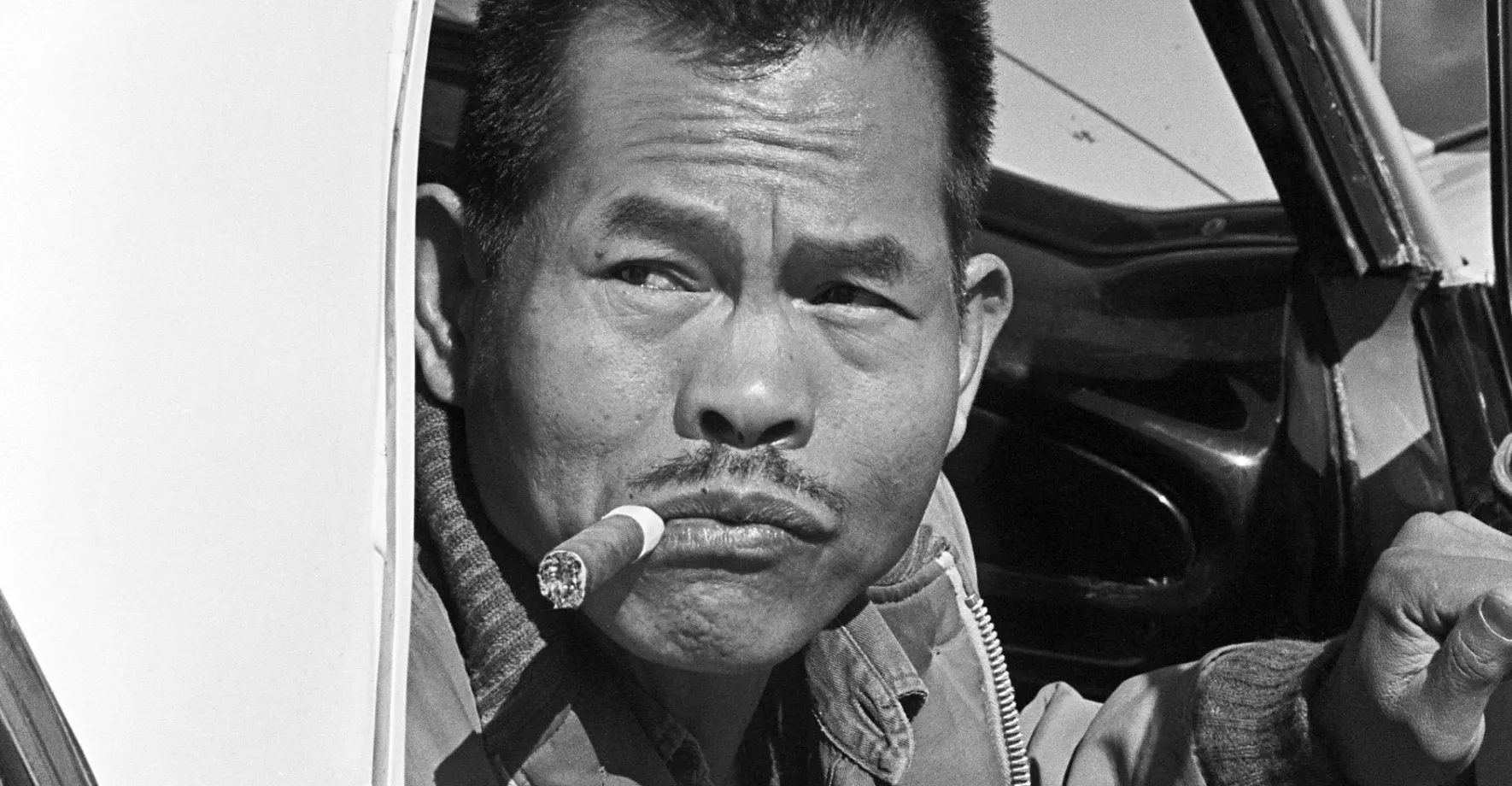

A natural leader, Itliong was often revered as a kuya, or “Filipino older brother.” He defied the rules of what a political activist should look like. Referred to as “Seven Fingers,” after losing three fingers in an accident, Itliong dressed in casual clothes, was often smoking a cigar, and used loud and crude language.

After serving in the U.S. Army during World War II, Itliong moved to California and started several labor efforts. In 1956, he founded the Filipino Farm Workers Union, which eventually ignited a series of strikes against the grape industry. Business owners responded to the strike by hiring Mexican-Americans to replace Filipino workers. This motivated Itliong to enlist Chavez and Huerta in the unification of farmers under one union movement: the United Farm Workers of America (UFW).

Itliong left the UFW in 1971 because of disagreements over how the organization was run. He continued leading labor efforts for Filipino workers, and died of ALS at age 63.

Itliong’s legacy lives on in countless ways, including the 2018 children’s book ‘Journey for Justice: The Life of Larry Itliong’ (written by Dawn Mabalon and Gayle Romasanta and illustrated by Andre Sibayan), and the 2015 California bill establishing October 25—Itliong’s birthday—as Larry Itliong Day

We are grateful for Itliong's work supporting the most vulnerable families and ensuring kids in the Filipino and Mexican agricultural communities had enough to eat.

Photo credit Welga