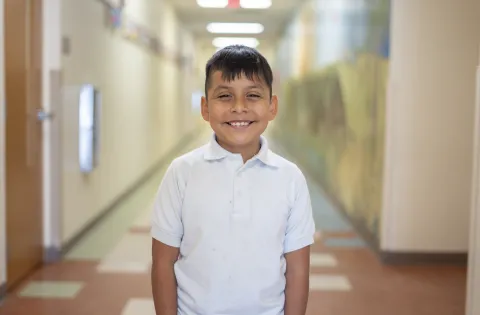

As part of our celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month, we’re sharing stories of Hispanic staff members highlighting their diverse experiences and what connects them to end childhood hunger. Today’s post highlights Stacie Sanchez Hare who serves as director at the No Kid Hungry Texas program department.

As I reflect on my journey as a proud Chicana from south Texas to New York City and back home again, I am humbled by the opportunities I had over the years and grateful for the example my parents set as civil servants and community leaders.

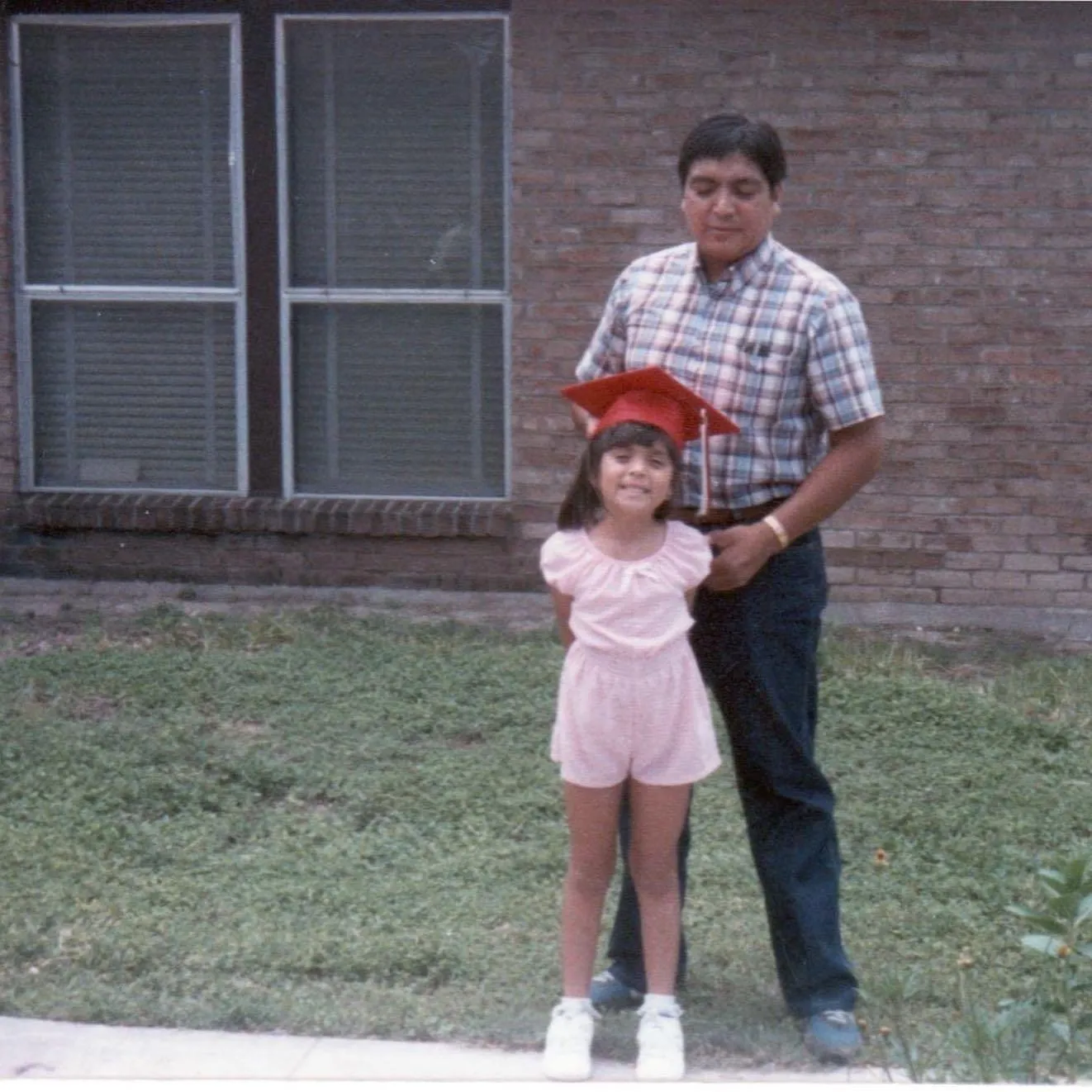

My dad, Augustine Sanchez, was a decorated Vietnam veteran and dutifully served as a letter carrier for the United States Postal Service for over 30 years. My mom, Esther Sanchez, started her career as a “cafeteria lady” at the local high school and went on to work for 24 years as a librarian aide with an emphasis on serving children who speak Spanish. They were eucharistic ministers in our church and influential to me understanding my identity and inspiring me to serve my community through my work at No Kid Hungry.

As a Mexican American growing up in south Texas, representation in national media or pop culture was scarce. I mostly saw people like me being portrayed as gang members, criminals or domestic workers with heavy accents. Mostly, it felt like being “Mexican” was a bad thing and as a result, I moved closer to whiteness and learned to code-switch.

However, there was one prominent shining star in my universe: the “Queen of Tejano Music,” Selena. Her short life story of adversity and resilience resonates strongly among the Hispanic community and is a point of pride among many Mexican Americans.

One of my favorite scenes from the 1997 biopic, Selena, featured a young Jennifer Lopez in the titular role, talking with her brother and dad about what it means to be Mexican American.

“Being Mexican American is tough. ... We’ve gotta be twice as perfect as anybody else,” grumbles Selena’s dad, played by Edward James Olmos, to his daughter. “I mean, we gotta know about John Wayne and Pedro Infante. We gotta know about Frank Sinatra and Agustín Lara. We gotta know about Oprah and Cristina.... We gotta be more Mexican than the Mexicans and more American than the Americans, both at the same time. It’s exhausting!”

I finally felt seen. I had the same conversation with my father and he emphasized that things would be even more challenging because I am a woman. Being a “hyphenated” American has been a journey. I often make this point to my Irish-American husband that his “Americanness” is never in question. He can identify as Irish and everyone assumes that he is American.

Eva Longoria recently remarked on her challenges of “straddling the hyphen line” on The Daily Show with Trevor Noah. “I am 100% Mexican and 100% American at all times," she said. I love enchiladas and burgers… It’s confusing!”

These sentiments closely capture my feelings and struggle to be proud of my identity. I also love hot dogs and breakfast tacos. I grew up listening to Janet Jackson, Madonna and the Tejano music that played at countless weddings, quinceañeras, and other family celebrations. I learned in English at school and heard Spanish at home. As Eva and Abraham said, it was exhausting and confusing.

I have endured countless microaggressions. When my son was a baby in New York City, I was asked by complete strangers if I was his nanny or if he was adopted. At the weddings of white friends, the father of the groom once said something to me like how many Mexicans worked at his factory and they were such hard workers. He meant to compliment me, so I smiled graciously instead of opting into a teachable moment. When I would disclose my race and ethnicity on a first date, I have been met with comments like, ‘you’re so tall’ or ‘your English is great.” I’m 5’6 and English is the only language I speak fluently.

My whole life, most people who don’t identify as Latinx, would pronounce my last name as SAN-CHEZ (like SANta Claus). At my first professional job, I summoned the courage to gently correct people and ask them to pronounce my name correctly. I have initiated conversations with my family and colleagues about the pervasiveness of colorism and anti-blackness in our communities. There have been many struggles and also breakthrough moments of growth.

Throughout my life, and sometimes unbeknownst to me, I have been on a journey to unravel my identity. I now identify as a person of the global majority, not a minority. I have committed to learning more about how systems of oppression are working as designed and how much of my own cultural history has been revised to portray non-white folx as inferior. As the Texas director, I am proud to lead a team composed of people of the global majority and authentically engage communities through an asset-based lens.

Now that I am the *grownup* who is planning family events, I strive to cultivate inclusive spaces that honor and celebrate my culture and others in all spaces. This week, we started our weekly check-in meeting by talking about Diez y Seis de Septiembre and Yom Kippur. At home, our family participates in a tamalada during the Christmas holidays. This year, we will create ofrendas for family members that have passed to honor and celebrate the lives they lived. I have proudly planted my American Serape flag in my subdivision and committed to my own journey and learning to love myself exactly as I am—100% Mexican and 100% American, at all times.